Home > About Us >Raudi > Clicker Training 101

Clicker Training 101

My interest in the theory behind the practice of clicker training materialized in 1992 when I was working on my Ph.D. in Composition and Rhetoric. I was enrolled in Classical Rhetoric and attempting to comprehend Aristotle’s Poetics. This interest has since resurfaced repeatedly. In April, 2010, I wrote the following essay about my experiences with this particular training technique.

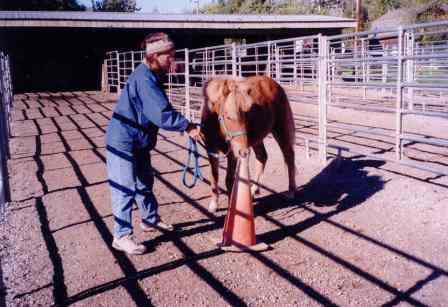

My lagging attention was piqued when I came to the part of the text in which he writes about what he calls “the click of recognition,” that is the instantaneous feeling that one gets when they’ve made an all-important connection. This so-called ahh haa moment is often compared to seeing a light bulb go on. Other terms that are used to describe this are “Eureka!” and “By George, I think I’ve got it!” Aristotle didn’t elaborate, but we all know that deep-seated sense of self-satisfaction that usually follows revelatory moments. We internalize what we learn and later make seemingly tangential connections. My graduate school course curriculum was set, so all I could do was take notice when related information crossed my path. One such work was Dr. Robert P. Crease’s essay entitled “The ‘Eureka!’ Moment Revisited.” Crease concedes that there is much to be learned about the nature of the discovery process and in addition, that “it’s still one of the most mysterious and controversial subjects in the philosophy of science.” He notes that “some scholars seek to create a ‘logic of discovery’ based on the formation of hypotheses while others such as Arthur Koestler describe the psychological conditions that favor the sudden insights which they call “Eureka” moments. Crease writes, “I believe discovery is better understood as an instance of recognition—and that the writings of ancient authors on this subject can prove surprisingly useful in helping us understand the discovery process.” I remained riveted to my chair as Cease cited Aristotle, who in his discussion of tragedy, “defined recognition as a passage ‘from ignorance to knowledge,’ which can either come about as a complete surprise, or as the fulfillment of dawning suspicions.” Aristotle focused on recognition between persons, although he too indicated that one can also recognize objects, events, and rules. The Greek philosopher posits that recognition has three characteristics. First, it concerns something familiar; secondly, it’s the outcome of a quest in which one's knowledge grows progressively deeper; and thirdly, it has unanticipated consequences. Crease, elaborating on the third characteristic, says that “by the time we discover something our previous experiments or ‘putterings around’ have given us a backlog of relevant experiences. So when we eventually become confident about the discovery it’s because there has been a recognition of something with which we are already familiar with and which we already have experienced.” Crease adds that “recent literature on recognition has stressed that one has to be prepared for recognition, that recognition may be dim (incomplete, a vague feeling of knowing) or dawning (the movement from dim recognition to the explicit achievement of recognition.)” In 2000, I moved to Butte, Montana, and shortly thereafter, I began making a tentative foray into the realm of animal cognition. I acquired a six-month old husky-border collie cross, and then discovered that come, sit, stay, and heel weren’t in her vocabulary. Rainbow was extremely energetic, which was why I enrolled her in an agility class. My hopes of her being a tractable animal were dashed when on the first day of class she slipped her collar and coerced a Jack Russell Terrier into playing a lengthy game of dog tag. After, Pam (the head trainer) took me aside and said that she had some homework for me to do. I was dismayed for I’d hoped that Rainbow’s training would be easy, simple, and take place during the arena sessions. Pam didn’t give me any directives but instead handed me a copy of Jean Donaldson’s The Culture Clash. Donaldson’s premise is that we can change dog behavior for the better through the use of positive reinforcement. The animal behaviorist had made a name for herself by putting theory to practice through the use of a clicker, a hand-held device that makes a click when pressed. The clicker acts as a bridge signal by immediately “telling” the animal (or person) that yes, you are doing the right thing. Donaldson says that one can use their voice as a bridge signal; however, the immediacy of the clicker is key because the alert is instantaneous. I’d been gung ho about the concept of clicker training but became less so after trying this out on Rainbow. I had a hard time understanding some of the terminology, and as well, some of the intricacies that are involved. For example, I’d click when Rainbow heeled, and then reinforce. However, I wasn’t sure what to do when she resumed pulling. Pam, who’d never before met the likes of Rainbow, was no help at all. My skepticism about clicker training increased after I began doing web-based research. Training methods that are supposedly novel, easy to implement, and promise a quick fix have always made me suspicious. Clicker Expos, email chat lists, and the promise that all behavioral issues can be solved with the use of clicker training increased my skepticism, as did the fact that the so-called experts downplayed its more deleterious aspects. I also began struggling with the very valid claim that the reliance upon clicker training, an operant-conditioning based technique, is indicative of the fact that humans and animals have no free will. This idea has been put forth by those such as B.F. Skinner, who while he didn’t use a clicker, suggested that the operant is exclusively responding to controlled and uncontrolled external stimuli. This implies that all creatures great and small are mere automatons. I, who craved that supposedly non-existent deeper connection, wanted to think otherwise. My animal-behavior related interests first centered on dogs but soon became broader in scope. The agility class was situated in a horse arena, and there a childhood interest in horses was rekindled. I dispensed with the agility and resumed taking riding lessons. A year after this, I moved to Alaska. I first took horse training classes at the local college and then bought an eight month old horse. My wanting to find a less adversarial way of working with Raudi prompted me to reconsider clicker training. Coincidently, Shawna Kareesh, the co-author of You can Teach Your Horse to do Anything, was scheduled to do a clicker training clinic in Homer. I audited this and then watched as during the next two days, Kareesh taught a Belgian mare to be accepting of an Australian rain slicker, a Welsh gelding to bow, and a Quarter Horse stallion to give its feet for cleaning. Kareesh’s work with a horse that was owned by a woman with a physical disability was the most impressive. By the end of the second day, the horse was responding to the down command, which enabled the rider to climb up on to mare’s back at ground level. As is often the case after attending clinics, I asked myself, where do I begin? I started with what seemed to me to be the most simple and straightforward aspect of clicker training; targeting, a practice in which the trainer teaches the animal to touch and then stay with a visible marker (such as a traffic cone). I was then, for the first time ever, able to note when one of my own animals experienced Aristotle’s so-called “click of recognition.” Raudi snuffled around for a bit, and then when she inadvertently touched the cone, she was told, via the clicker, that yes, she’d done the right thing. Of course, I reinforced this behavior by giving her a treat. Raudi then got the idea. The outward signs that followed her ahh haa moment were an animated posture, pricked ears, and a desire to again touch the cone. Once she had this down, I went to intermittent reinforcement; the premise here is that the so-called operant conditioner will better respond to a more sporadic reinforcement schedule. The resultant gesture has been described by Kareesh and other clicker trainers as being akin to that of a slot machine operator who hopes that the next pull of the level will enable them to hit the jackpot. I next took targeting a step further by training Raudi to touch an upright bicycle. My goal was to train her to stand by this target and to desensitize her to this strange object. Once she got this, I turned the bicycle wheel over and taught her to touch and then spin the front wheel. “Vanna White” then hit a stuck point. Raudi nudged the wheel, but seeing as no treat was forthcoming, explored other behavior-related options. She figured out that pawing, snorting, and lunging forward was unacceptable, as was evidenced by the fact that there was no click. However, going up to the wheel and pushing it with her chin was acceptable, as was evidenced by the fact that there was a click. As with targeting, this was yet another ahh haa moment. I used the clicker when training Raudi to walk on, whoa, stand, and turn on the forehand and haunches. I accomplished this by relying heavily upon the information contained in Alexandra Kurland’s book entitled Clicker Training for your Horse. Kurland, unlike Kareesh, IS a horse trainer who in fact has gained considerable notoriety by having trained Panda, a guide horse who functions as a Seeing Eye dog. In addition to doing clicker training, she relies heavily on the use of John Lyon’s pressure/release theory. I soon began riding Raudi. The use of the clicker subsequently enabled me get her past objects that otherwise would have caused her duress, some of which included a culvert that was suspended from a crane, and an open truck bed that contained three barking dogs. I was, on the day that I am now writing about, to learn that there is more to this clicker training business than I’d previously acknowledged. It was a blustery day; nevertheless, I’d decided to go for a ride. I took Raudi up a nearby dirt road and cued her to canter. Unbeknownst to us both, there was a wheelbarrow at the crest of the hill. Raudi first caught sight of the overturned object and approached it with her head held high. When, finally, we were within touching distance, I said touch. Raudi stepped forward and nudged the metal underpinnings. I clicked and gave her a treat. I took this teachable moment a step further by uttering the word “spin.” Raudi next gave the wheel a vigorous push with her nose. Her having differentiated between a bicycle and a wheelbarrow wheel indicated to me that she was capable of limited reasoning. This also refuted the claims of those behaviorists who contend that all animals are merely operants. However, the most consequential aspect of this impromptu experiment occurred on the return trip home. We later backtracked, and again came upon the wheelbarrow. My first thought was that Raudi would fail to recognize the wheelbarrow and refuse to go past it. My second was that she’d recognize it, and pitch a fit if I didn’t click and reinforce her. Raudi instead walked right past it. She’d recognized the object, and figured out that the absence of a click indicated that no reinforcer was coming. This was all well and good, however, it also verified that I’d hit a career-related impasse. My long standing interest in human cognition had somehow been superseded by an all consuming interest in animal cognition. My Ph.D. was in Composition and Rhetoric, which was a teaching-based degree. However, I was not able to find work teaching writing at the college level in Montana or Alaska. And so, while I’d enjoyed working with humans and animals, the former had somehow been aced out of the equation. I was, for a year, in the dark, as I attempted to figure out what to do next. This was not a good time in my life. However, I took solace in the works of others who in their lives hit and then moved beyond stuck points. For example, in the introduction to his book Happy to be There, Garrison Keilor writes in a very eloquent fashion about his failings as a novelist. Each day he’d sit at his computer and attempt to write. At about the same time, he began noticing a child sitting across the way. Keilor found him comparing himself to this child, and finally conceded “there’s no difference between a wannabee writer and a fat child sitting on a stoop. No difference at all.” He then changed career path by combining his interest in radio and writing. The end result was A Prairie Home Companion. My breakthrough occurred this past semester as I was taking a two credit course in which the first month’s focus was on animal behavior. A homework assignment lead me to researching aggression in bulls. I learned some things that I already knew, which is that male bovines are unpredictable, dangerous, and should be approached with caution. I also learned some things that I didn’t know. For example, a bull that’s hand raised will often assert its dominance over a human, who it thinks is another bull. Research often begets more research, which was why after I exhausted this particular topic I began reading up on the subject of aggression in horses. My course textbooks, two of which included Paul McGreevy’s Equine Behavior: A Guide for Veterinary and Equine Scientists and Katherine A. Haupt’s Domestic Animal Behavior had considerable information about the overt signs of aggressive behavior. In particular, McGreevy does an excellent job of describing the overt signs of aggressive behavior. For example, horses, says McGeevy may (among other things) “show their displeasure with other horses by biting, lunging, nipping, pawing, and stomping. They may also take threat positions, which are an indication that they may strike, bite, or grasp their adversary.” I kept going with this particular line of intellectual inquiry because I intuitively knew that while this interest was specifically related to animal cognition, that the people element would eventually make itself apparent. Further research revealed that some, like John Ledoux, had done considerable research on the role of aggression and fear as this relates to the amygdala, a structure in the limbic system, or oldest part of the brain. Defined, the amydgala is the name “given to a collection of nuclei found in the anterior portions of the temporal lobes in the brains of primates. The walnut-sized structure in the forebrain receives projections from frontal cortex, association cortex, temporal lobe, olfactory system, and other parts of the limbic system. In return, it sends its afferents to frontal and prefrontal cortex, orbitifrontal cortex, hypothalamus, hippocampus, as well as brain stem nuclei.” Ledoux, who is a neuroscientist at New York University, is reputed to be a pioneer in fear response. He believes that “emotions are hard wired biological functions of the nervous system that evolved to help animals to both survive in hostile environments and to procreate.” Fear he says “Is the product of the neural system that evolved to detect danger and that is causes an animal to make a response to protect itself.” LeDoux contends that the amygdala “assesses the perceived threat and triggers changes in the inner workings of the body’s organs and glands, stimulating the emotional and physical response of flight or flight. This is a rapid, non thinking reaction involving the secretion of cortisol, which causes an increase in glucose production, providing the necessary fuel for the brain and muscles, enabling them to deal with stress.” LeDoux adds that “neuroanatomists have shown that the pathways that connect the instinctive amygdala with the thinking brain (the cortex) are not symmetrical. The connections from the cortex to the amygdala are considerably weaker than those leading from the amygdala to the cortex. This is probably why once a fight or flight response is aroused, that it’s hard to turn off.” LeDoux’s findings coincided with what Temple Grandin says in Humane Livestock Handling: Understanding Livestock Behavior and Building Facilities for Healthier Animals, which is that the flight response tells horses to get a safe distance before taking time to analyze things, which may explain why they turn around after they bolt. They then have the safety of distance to take in more information and analyze what’s going on. The question that came to mind after internalizing all the above was, might a connection be made between the role of the amygdala and the use of the clicker? I determined that the answer was yes after Googling the words “amygdala,” and “clicker.” Karen Pryor is perhaps the best known advocate of clicker training. She, who used to be a dolphin trainer, has written several books on the subject including Don’t Shoot the Dog and Lads before the Wind. In an article on this very subject, Pryor mentioned having recently given a talk to the Association of Pet Dog Trainers about advances in clicker training. She was quick to acknowledge that the work of German scientist Barbara Schoening had influenced her thinking. Schoening, who is a veterinary neurophysiologist in private practice, enabled Pryor’s to ascertain that there’s a relationship to be made between clicker training and research on stimuli and the limbic system. Pryor notes that research in neurophysiology has identified the kinds of stimuli—bright lights, sudden sharp sounds—that reach the amygdala first, before reaching the cortex or thinking part of the brain. The click, she says “is that kind of stimulus.” Other research, particularly on conditioned fear responses in humans, shows that these also are established via the amygdala, and are characterized by a pattern of very rapid learning, often on a single trial, long-term retention, and “a big surge of concomitant emotions.” Pryor seemed to me to have advanced LeDoux’s belief that the amygdala is central to fear as well as to joy. She writes “We clicker trainers see similar patterns of very rapid learning, long retention, and emotional surges, albeit positive emotions rather than fear.” She and Schoening hypothesize that the clicker is a conditioned 'joy' stimulus that is acquired and recognized through those same primitive pathways, which help explain why it is so very different from, say, a human word, in its effect. Pryor also believes that the sound of the clicker is key to its effectiveness. She writes “another contributing factor to the extraordinary rapidity with which the clicker and clicked behavior can be acquired might be that the click is processed by the CNS much faster than any word can be. Even in the most highly-trained animal or verbal person, the word must be recognized, and interpreted, before it can 'work;' and the effect of the word may be confounded by accompanying emotional signals, speaker identification clues, and other such built-in information.” Pryor stresses that this claim is a working hypothesis that’s “based on various previously unconnected bodies of research and concludes her article by acknowledging that “more research needs to be done in this area.” As I read the end portion of Pryor’s paper, I sensed that there was a connection to be made between the literal and the figurative click as these occur in both animal trainers and in the animals themselves. My hunch was verified as I read her latest book, which is entitled Reaching the Animal Mind. For example, in Chapter Eleven, entitled “People” Pryor writes about coaches using the clicker to train athletes, in this particular instance, gymnastics students. Rather than use words, the click indicates to the performer that they’re making the right move. Pryor says that for older athletes the primary reinforcer is often instantaneous success. And younger students may earn tokens or move beads, which they might later trade in for a more tangible reward. Pryor’s question, which was mine as well, was why does this work so well? Her answer is that “tagging, when properly used, is a conditioned reinforcer. Thus it travels on the old, direct path through the amygdala, bringing with it instant learning, long retention, and a sense of elation: a thrill.” Reading this quote brought me full-circle. The students (in conjunction with the use of the literal clicker) are experiencing the figurative click of recognition. So yes, operant conditioning can be used to train animals and people. Works Cited

Crease, Robert. P. “Discovery: The Eureka! Moment Revisited,” R&D Innovator 2:8 (August, 1993): 9-10. Grandin, Temple. Humane Livestock Handling: Understanding Livestock Behavior and Building Facilities for Healthier Animals. North Adams, MA: Storey, 2008. Houpt, Katherine A. Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists, 4th ed. Ames: Blackwell, 2005. Karrasch, Shawna, and Vinton Karrasch. You Can Teach Your Horse to do Anything: On Target Training: Clicker Training and Beyond. North Pomfret, VT: Traflagar Square, 2000. Kurland, Alexandra. Clicker Training for Your Horse. Surrey, UK: Ringpress Books, 2004. Kurland, Alexandra, www.Guidehorse.org LeDoux, John “Emotion, Memory, And The Brain: What the Lab Does and Why We Do It.” LeDoux Laboratory, Center for Neural Science: New York University. http://www.cns.nyu.edu/ledoux/overview.htm McGreevy, Paul. Equine Behavior: A Guide for Veterinarians and Equine Scientists. New York: Saunders, 2004. Pryor, Karen. Don’t Shoot the Dog!: The New Art of Teaching and Training. New York: Random House, 1999. Pryor, Karen. Reaching the Animal Mind:

Clicker Training an What it Teaches us About All Animals. New

York: Scribner, 2009. |

Alys

Pete

Raudi

Form

and Function

Gerjun's Decision

Bolting

Chafa Chafa

Clicker Training

Trailer Training

Lessons

1

Lessons 2

Lessons 3

Lessons 4

Maresville

Minus Eight

Snow Day

Siggi

Tinni

Bootleg

Rainbow

Jenna

Goats

Chickens